There is a reason we have statutes of limitation and judges disallow almost all hearsay testimony. The accuracy of memories fade with time and twice-told tales are often riddled with ambiguities and inconsistencies.

As a historian, I often cringe when an account of an event that took place several decades ago is recalled either in written reminiscences or oral interviews by people who may or may not have even witnessed it. It is not that I believe the person recalling the event is fabricating their accountings, it is simply that the facts as they present them may be somewhat embellished or not always be correct.

Diaries and journals written at the time an event occurs are generally fairly accurate. Memories are fresh in the writer’s mind and mistakes regarding times, dates, and other critical data are usually minimal. Even years later, large life-impacting events such as the Kennedy assassination in 1963 and the downing of the World Trade Center towers on 9-11 generally illicit fairly accurate recollections from people who lived through them. Descriptions by ex-workers in now defunct manufacturing jobs usually remain reliable as they describe repetitive processes that took place over a number of years. However, smaller, less meaningful life experiences have a natural tendency to either shed important details or somehow take on interesting new ones as time goes by. Reminiscences and oral interviews about many of life’s experiences become less reliable from a factual perspective the longer the time interval between an event and its recounting.

We all have an Uncle Leo or an Aunt Josephine who spins an interesting tale about the past. Often, the more these folks age, the better their stories become. For those listeners with good memories who have heard their stories before, they might notice that Uncle Leo’s winter walk to the schoolhouse occurred in increasingly cold temperatures and deepening depths of snow that lasted later into the spring. And Aunt Josephine may have turned down three incredibly handsome well-to-do romantic suitors rather than the one poor youth who failed to win her affections before she married Uncle John in her initial recounting from a few years back. The over-all story might not change that much, just some of the facts. This is all fairly harmless – unless you are hearing it for the first time in its latest incantation and are willing to accept it as being factual.

None of this is meant to suggest that stories told about things that happened thirty, forty, or even fifty or more years before should be totally discarded. They simply need to be taken for what they are – someone’s precious memories. Whatever new facts that may be gleaned from them need to be carefully examined and corroborated prior to being relied upon as being factual.

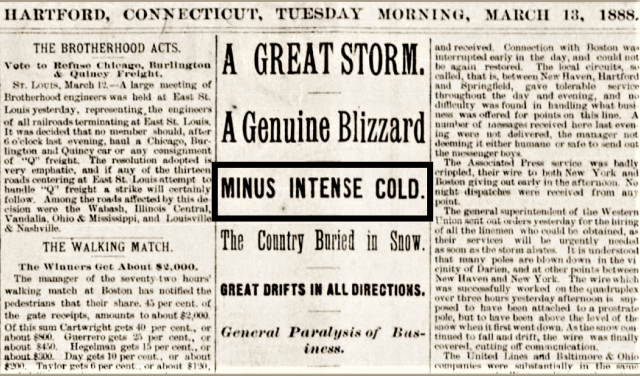

Since we have experienced a rather large snow event this past week, I am reminded of an accounting by one-time Redding resident Helen Nickerson Upson that was published over 60 years ago in the Redding Times. It has since been oft quoted in dozens of articles about the Blizzard of 1888. The piece itself is well-written and interesting to read. It reads as a first-hand accounting of the events that began on March 11, 1888 and is presented exactly as originally published and in its entirety below:

That Famous Blizzard of March 1888

by Helen N. Upson in the 1960 Redding Times

On the eleventh of March 1888, when Dad came in to breakfast from helping with the morning chores at the barn, he commented on the amazing mildness of the weather-the unseasonableness of conditions in nature. The sun shone brightly and the temperature at 8 AM was 62 degrees Fahrenheit. Here and there a few small patches of dirty, slushy snow remained, all the ponds were open, and no traces of ice bordered the streams.

In the marshes, swamp peepers were in full voice and male red-winged blackbirds were sounding a chorus of “Oak-a-lees” from the swamp maples. Pussy willows were uncovering their furry coats as from a lofty perch a song sparrow sang lustily his “Cheer-cheer-very-merry cheer-’tis springtime all the year” Which was misleading, to say the least.

There was a flash of blue as the male bluebird swiftly passed and came to rest on an old nest stub calling wistfully his oft repeated, “chur-wi.” Sap was dripping freely from bark lesions on the old bride-maples, and streamlets in the gutters gurgled gaily. Spring was definitely in the air bringing along with it evidence of Spring Fever. Dad became interested in seed catalogues and Spring planting while a desire to push housecleaning along, gripped my mother.

About 10 am Mother ordered one of the horses brought from the barn as she felt the urge to hurry to Danbury to start her Spring shopping. When she left she was wearing a winter coat but by noon the temperature had climbed to close to 70 degrees and she shed the coat for a light wrap. So often she spoke of the mildness, quiet and beauty of that day.

Quick Weather Change

Next morning-how different! Overnight there had been a radical change. The sky was overcast with heavy, sullen clouds, the mercury had catapulted to low levels and the air was filled with large snowflakes, blown in a vigorous breeze out of the north-east which was speedily increasing in velocity. The voices of birds and peepers, so evident a few hours before, were silent. There was no more open water. The surfaces of the ponds and streams were now congealed with a sheath of ice growing thicker as the cold increased.

Few valuable meteorological instruments were at hand to help in forecasting weather at that time, so even the weather bureau was entirely unprepared for the violence of the storm which was coming in out of the northeast. That morning men had gone to work as usual and children had attended school but before noon teachers became alarmed and closed the schools, shops shut down and many teamsters left the highways and sought shelter for man and beast. Children, men and horses were everywhere struggling against the driving, blinding, drifting snow. The power of the wind was terrific and those striving to face it were unable to breathe.

Several Redding people were unable to reach home. Many were taken in and furnished shelter while others were lost in the storm. One of our neighbors tried to get to his house near the Center from his place of employment in Sanfordtown but lost his way. His anxious wife started from home to find him but she, too, became lost. The bodies of both-more than a mile apart-were found under the snow during the spring thaw.

Mike Flood, local blacksmith was struggling against the storm in his effort to reach his home a short distance below the Center when he was overcome. He sought shelter in the lee of a tree, but from her window Mrs. Wakeman-wife of the local doctor-saw him plunge forward, face down into the snow. Unconscious he was dug out from the drift by the doctor and a young roomer there and carried into the Wakeman home where he was cared for until after the storm.

Ridge Got Brunt

For nearly three days the blizzard raged. People dying during the interval were wrapped in sheets and buried beneath the snow until they could be properly cared for. The winds reached terrific gale force and temperatures along the limestone ridge-upon which Redding rests- reached 42 degrees below zero.

Press accounts at that time quoted weather experts as saying that the storm spent its most violent efforts along this ridge. Windowpanes were frequently broken or blown in, shingles and clapboards were commonly ripped off, and snow drifted through every crack and crevice in any building in the town – homes included. Many stock barns, believed to be weather-tight, contained destructive quantities of snow.

On the modern, well-constructed and cared for Rumsey Dairy Farm snow was found to be so deep in the stables that cows and horses stood to their middles in it and many cows on this and other farms had to be slaughtered because their bags were frozen. After the storm drifts reaching second story windows were frequent, in orchards just the tips of the upper branches of the apple trees protruded from these small mountains of snow and the telegraph service was crippled, as everywhere, wires were down. There were no telephones in those days.

Animals Survive

On one farm a large flock of sheep was buried under the snow. The living animals were located by breathing holes on the surface. Many of the flock were dead but the several had survived by eating wool from the backs of their dead companions. In fact, all over town such animals as sheep, pigs and goats, buried under the snow, were located by surface breathing holes. This resulted in “hibernating” domestic animals of the above types, with turkeys, chickens, geese and even a few calves, being dragged into house cellars to thaw out.

I well recall an old lady telling me when I was in my teens, that during that storm her husband dragged into their cellar three unconscious pigs, a calf, a goat, chickens, ducks, geese, and turkeys that appeared to be dead. She related that before morning they commenced to wake up and were hungry. Their racket was equal to that of a zoo on fire.

Transportation Halted

Roads presented a terrific problem. As there were no telephones communication was entirely on foot or on snowshoes. Every farmer owning a yoke of oxen and an ox sled, helped to “break out the roads.” It required three yokes of oxen and six men on a sled to form a crew.

Usually a strong, heavy pair of Devons were chosen as the “lead” pair and they, with persistent urging, floundered into the drifts as far as they could possibly go. When they stopped the men dug and many drifts had to be tunneled. Later, when thaws came roofs of these tunnels caving in caused more trouble and plenty of shoveling. Everywhere wagons with horses removed were left along the highways remaining until dug out by these volunteer road crews.

No trains were running between Boston and New York or south of Pittsfield-they were all stalled along the line. People traveling on these stalled trains related tragic tales of suffering from cold and lack of food.

Slow Thaw

Although the storm arrived late, snow melted very slowly that year on the Redding hills and lingered long in the shadow of overhanging cliffs and in sheltered ravines. On July 4th of that blizzard year, my father gathered enough snowy ice from a sheltered ledge in what was then, Redding Glen, to make a five-gallon freezer full of ice cream.

An old timer born before 1800 declared that he had never before on land or sea (he was a retired sea captain) seen a storm a severe as this one. “But,” he added, “in many ways the year known as ‘1800 and Freeze To Death’ had it beaten.” That was the year 1816 when the weather was worse because every month of the year had a killing frost and the August freeze up was so severe that the trees, after losing all their leaves, were unable to grow another crop. As a result, by Spring numerous trees were dead.

By the time she penned the above reminiscence, Helen Nickerson Upson was 72 years of age and well known as a retired school teacher and the former curator of the Botanical Department at Yale. It is doubtful that anyone would have challenged her accounts regarding what was once deemed the “Great White Hurricane of 1888”. If you had never read much about Blizzard of 1888, you would likely find the above account to be a most interesting story and if you had subsequently run across it many years later on the state sponsored website, Connecticuthistory.org, put out by the office of the Connecticut State Historian, you should rightly expect it to be fairly accurate accounting of that event. Except it is not, and here are just a few of the reasons why.

First, the entire recollection reads as it it were written in the first person by someone who lived through and witnessed firsthand the ordeal she described. But Helen Upson wasn’t yet born in March of 1888. She came into this world in June of that year, so her entire flowery introduction full of specifics about the birds and the peepers and the spring-like sunshine is nothing more than a whimsical account of how she thought that morning of March the 11th might have been. Everything else that followed is at a minimum a twice told tale. Once by whoever recounted the past to Helen and once by herself in her reminiscence.

The facts don’t add up to the reality of the day.

Helen tells of her dear mother ordering one of the horses from the barn on the day preceding the storm so that she might go to Danbury to begin her spring shopping. But March 11 was a Sunday. In 1888, retail stores in Danbury and every other town in Connecticut would have been shuttered on every single Sunday of the year. The Blue Laws of that era made Sunday operations illegal.

Nearly 70 degrees by noon. The Hartford Courant reported on March 13th that the temperature in Connecticut had been a relatively mild 45 to 50 degrees during the day on the 11th. Nowhere near 70.

Fast forward to Monday when several Redding residents were unable to navigate their way home through the blinding blizzard. According to Ms. Upson, an unnamed husband and his wife perished separately; he on his way home from work and she foolishly out looking for him. Their bodies were not found until the spring thaw. Perhaps these people remained unnamed because there is absolutely no written record of any Redding resident perishing during that storm, never mind a husband and his wife. That would also prove the statement: “People dying during the interval were wrapped in sheets and buried beneath the snow until they could be properly cared for,” to be false as far as Redding was concerned.

42 below zero temperatures on Redding Ridge. By her own account that would have amounted to a 112-degree temperature swing in only 24 to 30 hours, larger than any recorded in US history. On March 14, 1888, the Waterbury Evening Democrat reported the weather during the night of March 12th when the blizzard was at its peak: “The wind was blowing a 40-mile gale and the mercury was gradually going down, marking 9 degrees before morning.” The Hartford Courant’s March 13th article read: “The good thing about the storm was that the temperature was not near the zero point…The storm began early Sunday night with the temperature around 40 degrees.“

“I well recall an old lady telling me when I was in my teens, that during that storm her husband dragged into their cellar three unconscious pigs, a calf, a goat, chickens, ducks, geese, and turkeys that appeared to be dead.” Again an unnamed person telling a secondhand account of what appears to be at the very least, a greatly embellished tale. If the snow was that deep, the visibility so poor, and the temperature so low that the animals and fowl mentioned here were in a forced state of hibernation, how would they have been located beneath so much snow? It’s not unlikely that farmers began taking their livestock indoors as the storm grew in intensity, but locating five fairly good sized animals and what appears to be a multiple variety of fowl after they had reached the point of total immobility under several feet of snow is more than a suspect tale.

I’m sure that much of what Ms. Upson wrote about occurred, although likely to a far lesser extent. The issue is that it has been so often repeated that it is now treated as a factual accounting of a miserable storm that needed no embellishments with greater loss of lives, more snow, and temperatures so low that they rivaled all-time records.

The Blizzard of 1888 paralyzed the East Coast from the Chesapeake Bay to Maine. Telegraph and telephone wires went down, isolating New York, Boston, Philadelphia, and Washington for several days. Some two hundred ships were grounded, and scores of seamen lost their lives. Deep snow and high winds immobilized city fire departments, and property loss from fire alone was estimated at about $25 million. Overall, more than 400 deaths were reported.

Those are all facts, not secondhand accounts recorded by someone who wasn’t even born yet.

At the Historical Society of Easton, we have a few dozen oral histories that we have recently had digitized as a means of preservation. A few have been previously transcribed, and it is our goal to ultimately transcribe the rest. Some are quite interesting, others more mundane. But the issue with all of them is the need to fact check certain information before we share them with the public. Once a historical society or any other community organization puts their collection of oral histories or written reminiscences before the eyes and ears of the public, they can be seen as endorsing the content as being factual, regardless of whether or not that is the case. As responsible members of the community we need to be mindful of disseminating personal historical accounts of past events that may in fact be inaccurate. Separating fact from fiction is sometimes a daunting and nearly impossible task, but as custodians of the past, it’s a task we are obligated to perform.